Chartres Cathedral

| Chartres Cathedral* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|

|

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 81 |

| Region** | Europe |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. |

|

The Cathedral of Our Lady of Chartres, (French: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres), a Latin Rite Catholic cathedral located in Chartres, about 80 kilometres (50 mi) southwest of Paris, is considered one of the finest examples in all France of the Gothic style of architecture. The current cathedral is one of at least four that have occupied the site.

From a distance it seems to hover in mid-air above waving fields of wheat, and it is only when the visitor draws closer that the city comes into view, clustering around the hill on which the cathedral stands. Its two contrasting spires — one, a 105 metre (349 ft) plain pyramid dating from the 1140s, and the other a 113 metre (377 ft) tall early 16th century Flamboyant spire on top of an older tower — soar upwards over the pale green roof, while all around the outside are complex flying buttresses.

Contents |

History

The cathedral was the most important building in the town of Chartres. It was the centre of the economy, the most famous landmark and the focal point of almost every activity that is provided by civic buildings in towns today. In the Middle Ages, the cathedral functioned sometimes as a marketplace, with the different portals of the basilica selling different items: textiles at the northern end; fuel, vegetables and meat at the southern one. Sometimes the clergy would try to stop the life of the markets from entering into the cathedral. Wine sellers were forbidden to sell wine in the crypt, but were allowed to do business in the nave of the church and avoid the taxes which they would have to pay if they sold it outside. Workers of various professions, such as carpenters and masons, gathered in the cathedral seeking jobs.

Pilgrimages and the legend of the Sancta Camisa

Even before the early Gothic cathedral was built, Chartres was a place of pilgrimage. When ergotism (more popularly known in the Middle Ages as "St. Anthony's fire") afflicted many victims, the crypt of the original church became a hospital to care for the sick.[1]

The church was an especially popular pilgrimage destination in the 12th century. There were four great fairs which coincided with the main feast days of the Virgin: the Presentation, the Annunciation, the Assumption and the Nativity. The fairs were held in the surrounding area of the cathedral and were attended by many of the pilgrims in town for the feast days and to see the cloak of the Virgin. Thus, for hundreds of years, Chartres has been a very important Marian pilgrimage center; today the faithful still come from the world over to honour the relic.

According to legend, since 876 the cathedral's site has housed a tunic that was said to have belonged to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Sancta Camisa. The relic had supposedly been given to the cathedral by Charlemagne who received it as a gift during a crusade in Jerusalem. In fact, the relic was a gift from Charles the Bald and it has been asserted that the fabric came from Syria and that it had been woven during the first century AD.

Cathedral Building History

There have been at least five cathedrals on this site, each replacing an earlier smaller building that had been destroyed by war or fire. It was called the 'Church of Saint Mary' in the eighth century, and in 876 Charlemagne's grandson, Charles the Bald, gifted the Virgin's great relic, the Sancta Camisia, to the cathedral. It is believed to be the one that Mary wore when she gave birth to Christ.

This veil is now housed in the cathedral treasury. The present dedication to 'Beata Maria Assumpta' probably dates from this gift.

The earlier church had been destroyed by the Danes in 858. There was another fire in 962, and a more devastating conflagration in 1020 after which Bishop Fulbert reconstructed the whole building. Most of the present crypt, which is the largest in France, remains from that period.

Construction began in a blaze of enthusiasm dubbed the "Cult of the Carts". During this religious outburst a crowd of more than a thousand penitents dragged carts filled with building provisions including stones, wood, grain, etc. to the site.[2]

Bishop Fulbert established Chartres as one of the leading teaching schools in Europe. Great scholars were attracted to the cathedral, including Thierry of Chartres, William of Conches and the Englishman John of Salisbury. These men were at the forefront of the intense intellectual rethinking that we call the twelfth-century renaissance, and that led to the Scholastic philosophy that dominate medieval thinking.

In 1134 another fire damaged the town, and perhaps part of the cathedral. The north tower was started immediately afterwards, and when it reached the third storey, the south tower was begun.[3]

The sculpture of the Royal Portal was installed with it, probably just before 1140. It was once thought that this sculpture was intended for another place and moved here, but recent investigation has shown that all three doors and the magnificent figures around them were created for their present situation. The two towers were then completed fairly quickly and, between them on the first level, a chapel constructed to Saint Michael. Traces of the vaults and the shafts which supported them are still visible in the western two bays. The glass in the three lancets over the portals which once illuminated this chapel were installed in about 1145. The south spire is 103 meters high, and was completed before 1155.

Finally, on 10 June 1194 another fire destroyed nearly the whole of Fulbert's cathedral. The choir and nave had to be rebuilt, though the undamaged western towers and the Royal Portal were incorporated into the new works, as well as the old crypt. The present cathedral is only slightly longer than the earlier one.[4]

Construction proceeded quickly, with about 300 men on site at any one time. The south porch with all its sculpture was installed by 1206, and by 1215 the north porch had been completed and the western rose installed.[5] The high vaults were erected in the 1220s, the canons moved into their new stalls in 1221, and the transept roses were erected over the next two decades.

Each arm of the transept was originally meant to support two towers, two more were to flank the choir, and there was to have been a central lantern over the crossing - nine in all. The latter was eliminated in 1221, and the crossing vaulted over. Work continued in a desultory fashion on the six additional towers for some decades, until it was decided to leave them incomplete, and the incompleted cathedral was dedicated in 1260 by King Louis IX.[6]

Little has been done to the cathedral since then. In 1323 a new meeting house was constructed at the eastern end of the choir for the Chapter, with the Chapel of Saint Piat above that. This is today the cathedral treasury. Shortly after 1417 a small chapel was placed between the buttresses of the south nave for the Count of Vend6me. At the same time the small organ that had been built in the nave aisle was moved up into the triforium where it still is, though some time in the sixteenth century it was decided replace it with a larger one a raised platform at the western end of the building. To this end some of the interior shafts in the western bay were removed and plans made to rebuild the organ there. It was fortunate that this decision was reversed, for otherwise the wonderful glass in the western lancets would have been lost. Instead the old organ was replaced with the new one we know today.

In 1506 lightning destroyed the north spire, which was rebuilt by Jehan de Beauce. It is 113 meters high. He took seven years to carve the intricate and delicate stonework on this tower, and erect it. Afterwards he continued working on the cathedral, and began the monumental screen around the choir stalls, which was not completed until the beginning of the eighteenth century.

In 1757 the jubé screen between the inner choir and the nave was torn down, and the present stalls built. Some of the magnificent sculpture from this screen was found buried underneath the paving, and removed to the treasury. At the same time some of the stained glass in the choir clerestory was removed and replaced with grisaille, or grey glass, so that the canons could read their missals more easily. Then in 1836 the old lead and timber roof, known as the forest, was burnt out and rebuilt with copper sheeting on cast iron supports - at its time the largest span on the continent.

The cathedral has been fortunate in being spared the damage suffered by so many during the Wars of Religion and the Revolution, though the lead roof was removed to make bullets and the Directorate threatened to destroy the building as its upkeep, without a roof, had become too onerous. All the glass was removed just before the Germans invaded France in 1939, and was cleaned after the War and releaded. Since then the fabric has been lovingly tendered and repaired in a most scrupulous fashion to retain its original character and beauty.

The Master Masons

During a night in 1194 a disastrous fire raged through the town of Chartres, laying waste most of the houses and shops, and destroying much of its cathedral. As the smoke abated only the western spires remained above the charred and tattered walls. The townsfolk and the clergy decided, that the fire had been a sign from the Virgin herself, an injunction to rebuild Her House in the most marvellous manner possible.

For this they invited an architect from the region to the north-east of Paris, a talented man who had worked for the Cistercians and the Benedictine monks, as well as at the cathedral of Laon. He seems to have been a seriously philosophic man, skilled as a mason and with a considerable understanding of the Christian theology of his day. His name is unknown for all the documents have been lost, but he has been identified in sufficient locations to gain some idea of his standing and capacities. Lacking a documented name, one scholar has called him 'Scarlet'.[7]

A dozen years earlier he had begun the apse in the huge Cistercian Abbey of Longpont. This austere order imposed strict limitations on the masons who worked for them; but it seems that Scarlet may have influenced his patrons, for the plan of Longpont was unusual for the 1180s. Instead of the usual flat eastern end, Longpont has an ambulatory with seven chapels not unlike the plan Scarlet prepared for Chartres a little later.

Scarlet did not work long on the Chartres site, for the entire cathedral was constructed by teams of roving contractors who seem to have worked for as long as there was money, and then moved on to other sites. Nine major teams were involved it this great task. Though Scarlet's design influenced every master who followed him, each new master imposed his ideas on the cathedral plan whenever he could, and continued with his predecessor's concepts when he could not.

In spite of the constant coming and going of these different teams of men, nearly the whole of the cathedral was completed in thirty years. Building teams were large, perhaps consisting of 300 men, of which 50 would have been skilled masons and the key men in charge of the organization. This number could not have been left idle while the church waited for donations. Once the coffers were empty they would have left the site in a body, and found other employment. When enough money had collected to allow the church to re-engage masons, the last group was probably working at some other site, and a fresh team had to be found. Impermanency was normal, and everyone expected it.

There were also technical considerations, like the slow-setting lime mortar that could force the builders to leave. Even in the Royal works, where there were ample funds, builders were put off while the mortar set in the voussoirs of the arches or vaults. At the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris there may have been as many as five changes to crews for just these technical reasons. Changes in masters were expected by both the owners and the masters themselves. Their methods of design were evolved to cope with this situation, and to ensure that enough unity would be maintained between the working mason and his successor to prevent the design becoming totally chaotic.

This was a time of extraordinary building activity across the limestone region called the Paris Basin. Over 2,700 churches, chapels and cathedrals were built in this small area during the one century that separated the choir of Saint-Denis from the Sainte-Chapelle. Over 90 percent of all Early Gothic churches are found in the Paris Basin because it was here, and practically nowhere else, that the revolution in architecture was occurring.

A recent analysis of the costs of this ecclesiastic work showed that the quantity of building in the north around Soissons and was greatest in the 1170s and 1180s, while in the Ile-de-France construction peaked around 1220.[8] While the Soissonais was a-bubble with great buildings, churches in the area around Paris were relatively modest. It was in the north-east, therefore, that construction teams were assembled and trained. After 1190, as work declined in the north-east, these skilled men, complete with their followers, travelled great distances looking for work, and Chartres was one of them. And this is why most of the other buildings executed by the contractors or master builder who built Chartres are to be found to the north of Paris between Senlis and Reims.

The Nine Masters

Research conducted in the 1960s has shown that there were nine groups, or teams of masons, each under the control of one master mason, with their attendant quarriers, apprentices and so on. These teams, which may have numbered as many as three hundred men, seem to have arrived on the site as a group, and left together: the carving styles change at the same time as the architectural details.[9]

The unusual aspect of the medieval building process, which applies to the smallest church as much as to the greatest cathedral, was that these teams seldom stayed on the site for very long. One might work for a few months, the next for a couple of years, in an ever changing sequence that lasted throughout the many decades needed to construct the cathedral.

The first master was named Scarlet, since we did not know his name; he began work just after the fire in 1194. The second was Bronze and the third Olive, working around 1196. Probably in 1200 Scarlet returned to set out the south porch and the labyrinth. Olive returned some ten years later to redesign the clerestory windows, and the team we call Bronze worked nine times on the site between the fire and the completion of the main vaults.

For over thirty years the masters changed almost every year. The cause was probably money: they did not have the sophisticated funding techniques we possess, but relied on cash, and when there was money the hand work could be pushed on apace - but when there was none the builders had no choice but to pack up and find work elsewhere. And this they did.

Olive, for example, worked mainly along the Marne river, and at Rheims and Soissons, and on only three occasions moved out of this region to work at Chartres. Most of the work by the Bronze team is to be found in the hill district between the Aisne and Laon, though his characteristic style is to be found as far away as Longpont in the north-east and Mantes-la-Jolie, as well as at Chartres.[10]

It is by their style that we recognize them. This most exciting aspect of this research is identifying the hitherto anonymous architects of the Middle Ages by what we might call the thumb-print of each person. Every master had a unique approach to his profession, with his own way of creating the profiles and of arranging them into elements like windows and doors. Though there were changes with the passing years, each master's personal style tended to remain distinctly his during his lifetime.

There are still many gaps in our knowledge, but it is becoming increasingly clear that the extraordinary architectural inventions manifested during the century around 1200 stemmed from the creative endeavours of a few dozen men who travelled across great distances with their workmen. They gained an intimate understanding of their fellows by constantly being asked to continue with buildings which had been reared by others, yet every one of them maintained a strong, often idiosyncratic, manner of working that identifies him as clearly as the lines on our hands will identify us.

The cathedral is still the seat of the Bishop of Chartres of the Diocese of Chartres, though in the ecclesiastical province of Tours.

French Revolution

The cathedral was damaged in the Revolution when a mob began to destroy the sculpture on the north porch. This is one of the few occasions on which the anti-religious fervour was stopped by the townfolk. The Revolutionary Committee decided to destroy the cathedral via explosives, and asked a local master mason (architect) to organise it. He saved the building by pointing out that the vast amount of rubble from the demolished building would so clog the streets it would take years to clear away. However, when metal was needed for the army the brass plaque in the centre of the labyrinth was removed and melted down - our only record of what was on the plaque was Felibien's description.

The Cathedral of Chartres was therefore neither destroyed nor looted during the French Revolution and the numerous restorations have not diminished its reputation as a triumph of Gothic art. The cathedral was added to UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites in 1979.

Description

Plan and elevation

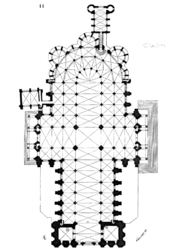

The plan is cruciform, with a 28 metres (92 ft) long singled-aisled nave, and short transepts (three bays deep) to the south and north. The east end is rounded with a double-aisled ambulatory, from which radiate three deep semi-circular chapels (overlying the deep chapels of Fulbert's 11th-century apse) and four much shallower ones, one of which was effectively lost in the 1320s when the Chapel of St Piat was built.

The cathedral extensively used flying buttresses in its original plan, and these supported the weight of the extremely high vaults, at the time of being built, the highest in France. The new High Gothic cathedral at Chartres used four rib vaults in a rectangular space, instead of six in a square pattern, as in earlier Gothic cathedrals such as at Laon. The skeletal system of supports, from the compound piers all the way up to the springing and transverse and diagonal ribs, allowed large spaces of the cathedral to be free for stained glass work, as well as a towering height.

The spacious nave stands 36 metres (118 ft) high, and there is an unbroken view from the western end right along to the magnificent dome of the apse in the east. Clustered columns rise dramatically from plain bases to the high pointed arches of the ceiling, directing the eye to the massive clerestory windows in the apse.

Windows

The cathedral has three large rose windows: one on the west front with a theme of The Last Judgment, one on the north transept with a theme of the Glorification of the Virgin, and one on the south transept with a theme of the Glorification of Christ.

Chartres is noted for its many large stained glass windows. Dating from the early 13th century, the glass largely escaped harm during the religious wars of the 16th century; it is said to constitute one of the most complete collections of medieval stained glass in the world, despite "modernization" in 1753 when some of it was removed by well-intentioned but misguided clergy. Of the original 186 stained glass windows, 152 survive. The windows are particularly renowned for their vivid blue colour, especially in a representation of the Madonna and Child known as the Blue Virgin Window, a traditional iconography known as the Seat of Wisdom. The Jesse Tree window is another noted window at Chartres.

Several of the windows were donated by royalty, such as the rose window at the north transept, which was a gift from the French queen Blanche of Castile. The royal influence is shown in some of the long rectangular lancet windows which display the royal symbols of the yellow fleurs-de-lis on a blue background and also yellow castles on a red background.Windows were also donated from lords, locals and tradespeople.

The windows also present the first European wheelbarrow.[11]

During the Second World War, most of the stained glass was removed from the cathedral and stored in the surrounding countryside to protect it from German bombers. The cathedral was used as a social club during the German occupation of France. At the close of the war, the windows were taken out of hiding and reinstalled.

Porches

On the doors and porches, medieval carvings of statues holding swords, crosses, books and trade tools parade adorn the portals. The sculptures on the west façade depict Christ's ascension into heaven, episodes from his life, saints, apostles, Christ in the lap of Mary and other religious scenes. Below the religious figures are statues of kings and queens, which is the reason why this entrance is known as the 'royal' portal. While these figures are based on figures from the Old Testament, they were also regarded as images of current kings and queens when they were constructed. The symbolism of showing royalty displayed slightly lower than the religious sculptures, but still very close, implies the relationship between the kings and God. It is a way of displaying the authority of royalty, showing them so close to figures of Christ, it gives the impression they have been ordained and put in place by God. Sculptures of the Seven Liberal Arts appear in the archivolt of the right bay of the Royal Portal, indicating the influence of the school at Chartres.

Statistics

- length: 130 metres (430 ft)

- width: 32 metres (105 ft) / 46 metres (151 ft)

- nave: height 37 metres (121 ft); width 16.4 metres (54 ft)

- Ground area: 10,875 square metres (117,060 sq ft)

- Height of south-west tower: 105 metres (344 ft)

- Height of north-west tower: 113 metres (371 ft)

- 176 stained-glass windows

- rood screen: 200 statues in 41 scenes

The school of Chartres

In the Middle Ages the cathedral also functioned as an important cathedral school. Charlemagne wanted a system of education for the French people in the ninth century, and since it was difficult and costly for new schools to be built, it was easier to use already existing infrastructure. So he ordered that both cathedrals and monasteries maintain schools. Cathedral schools eventually took over from monastic schools as the main places of education. In the 11th century the education system was controlled by the clergy in cathedrals such as Chartres. The cathedral itself symbolized the school. Many French cathedral schools had specialties, and Chartres was most renowned for the study of logic. The new logic taught in Chartres was regarded by many as being even ahead of Paris. One person who was educated at Chartres was John of Salisbury, an English philosopher and writer, who had his classical training there under the tutelage of Thierry of Chartres. According to Malcolm Miller, the school was responsible for the Neoplatonic symbolism of the cathedral's west façade.

In popular culture

Orson Welles famously used Chartres as a visual backdrop and inspiration for a montage sequence in his film F For Fake. Welles’ semi-autographical verse spoke to the power of art in culture and how the work itself may be more important than the identity of its creators. Feeling that the beauty of Chartres and its unknown artisans/architects epitomized this sentiment, Welles said:

Ours, the scientists keep telling us, is a universe which is disposable. You know it might be just this one anonymous glory of all things, this rich stone forest, this epic chant, this gaiety, this grand choiring shout of affirmation, which we choose when all our cities are dust; to stand intact, to mark where we have been, to testify to what we had it in us to accomplish. Our works in stone, in paint, in print are spared, some of them for a few decades, or a millennium or two, but everything must fall in war or wear away into the ultimate and universal ash: the triumphs and the frauds, the treasures and the fakes. A fact of life ... we're going to die. "Be of good heart," cry the dead artists out of the living past. Our songs will all be silenced – but what of it? Go on singing. Maybe a man's name doesn't matter all that much.

Joseph Campbell references his spiritual experience in The Power of Myth:

I'm back in the Middle Ages. I'm back in the world that I was brought up in as a child, the Roman Catholic spiritual-image world, and it is magnificent ... That cathedral talks to me about the spiritual information of the world. It's a place for meditation, just walking around, just sitting, just looking at those beautiful things.

In the film Two for the Road, Mark Wallace (played by Albert Finney) says to his wife, Jo (Audrey Hepburn):

Nobody knows the names of the men who made it. To make something as exquisite as this without wanting to smash your stupid name all over it. All you hear about nowadays is people making names, not things.

Joris-Karl Huysmans includes detailed interpretation of the symbolism underlying the art of Chartres Cathedral in his 1898 semi-autobiographical novel La Cathédrale.

Chartres was the primary basis for the fictional Cathedral in David Macaulay's Cathedral: The Story of Its Construction and the animated special based on this book.

Chartres was a major character in the religious thriller Gospel Truths by J. G. Sandom. The book used the Cathedral's architecture and history as clues in the search for a lost Gospel.

The cathedral is featured in the television travel series The Naked Pilgrim; presenter Brian Sewell explores the cathedral and discusses its famous relic - the nativity cloak said to have been worn by the Virgin Mary.

The cathedral now

At present, the west portal is under way with the restoration. According to a local bill board this will take place until summer 2011.

See also

- Roman Catholic Marian churches

- France in the Middle Ages

References

Bibliography

- Burckhardt, Titus. Chartres and the birth of the cathedral. Bloomington: World Wisdom Books, 1996. ISBN 0-941532-21-6

- Adams, Henry. Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1913 and many later editions.

- Ball, Philip. Universe of Stone. New York: Harper, 2008. ISBN 0-06-115429-6.

- Delaporte, Y. Les vitraux de la cathédrale de Chartres: histoire et description par l'abbé Y. Delaporte ... reproductions par É. Houvet. Chartres : É. Houvet, 1926. 3 volumes (consists chiefly of photographs of the windows of the cathedral)

- Fassler, Margot E. The Virgin of Chartres: Making History Through Liturgy and the Arts (Yale University Press; 2010) 612 pages; Discusses Mary's gown and other relics held by the Chartres Cathedral in a study of history making and the cult of the Virgin of Chartres in the 11th and 12th centuries.

- Houvet, E. Cathédrale de Chartres. Chelles (S.-et-M.) : Hélio. A. Faucheux, 1919. 5 volumes in 7. (consists entirely of photogravures of the architecture and sculpture, but not windows)

- Houvet, E. An Illustrated Monograph of Chartres Cathedral: (Being an Extract of a Work Crowned by Académie des Beaux-Arts). s.l.: s.n., 1930.

- James, John, The Master Masons of Chartres, West Grinstead, 1990, ISBN 0-646-00805-6.

- James, John, The contractors of Chartres, Wyong, ii vols. 1979-81, ISBN 0-9596005-2-3 and 4 x

- Mâle, Emile. Notre-Dame de Chartres. New York: Harper & Row, 1983.

- Miller, Malcolm. Chartres Cathedral. New York: Riverside Book Co., 1997. ISBN 1-878351-54-0.

Notes

- ↑ Favier, Jean. The World of Chartres. New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1990. p. 31. ISBN 0-8109-1796-3.

- ↑ Honour, H. and Fleming, J. The Visual Arts: A History, 7th ed., Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005.

- ↑ John James, "La construction du narthex de la cathédrale de Chartres", Bulletin de la Société Archéologique d’Eure-et-Loir, lxxxvii 2006, 3-20.

- ↑ John James, The contractors of Chartres, Wyong, ii vols. 1979-81.

- ↑ John James, The master masons of Chartres, London, NY, Chartres and Sydney, 1990, ISBN 0 646 00805 6.

- ↑ Favier, Jean. The World of Chartres. New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1990. p. 160. ISBN 0-8109-1796-3.

- ↑ John James, Chartres, les constructeurs, Chartres, iii vols. 1977-82.

- ↑ John James, "Funding the Early Gothic churches of the Paris Basin", Parergon, xv 1997, 41-82

- ↑ John James, The Template-makers of the Paris Basin, Leura, 1989

- ↑ John James, "The Canopy of Paradise", In Search of the Unknown, London, 2006

- ↑ "Wheelbarrow". John H. Lienhard. The Engines of Our Ingenuity. NPR. KUHF-FM Houston. 1990. No. 377. Transcript.

External links

- University of Pittsburgh photo collection

- Chartres Cathedral at Sacred Destinations

- (English) http://www.mymaze.de/chartres_technisch_e.htm (About the labyrinth)

- Details of the Zodiac and other Chartres Windows

- Description of the outer portals Retrieved 03-08-2008

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||